It was a lot of fun speaking to the Honors Students at the University of Rhode Island for their Colloquium on The Power Of Humor. First , I did a “Inside the Actor’s Studio” type session with the small group of honors students, and then in the evening, I gave a talk/lecture about Gender, Global Politics, Cartoons and Humor. They were a great audience, laughing at much of what I said and showed, and asked fantastic questions about the seriousness of some of what I discussed having to do with freedom of expression, global politics and gender.

One thing that I found interesting is that after each event–the small one and the larger–most, but not all, of the people who came up to talk to me afterwards were young men. I think men want to help.

Here is an interview I did with the campus paper about the event. And below is the text of my speech, without my oh-so humorous ad-libs and cartoons.

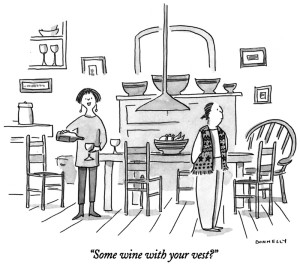

One young honor student named Nick wore a fancy sweater in honor of one of my cartoons that he saw while researching me beforehand.

Gender, Politics and Humor

“Humor can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind.” EB White

It’s true that it is not always satisfying to pick humor apart and analyze it. Many do, myself included, but we do it out of curiosity. And I think in examining humor, one doesn’t expect it to necessarily get funnier. We just learn something else.

What do we learn when we step back and look at humor? We learn about ourselves. What we laugh at tells us something—because its true, different people laugh at different things. We learn the good and the bad.

I have been drawing cartoons a long time, and about ten years ago, I began to look into the why of what I do. Two events in my life coincided at around the same time that caused a certain amount of introspection. Actually three– 9/11 was a turning point for me, as well. One was in 2005 I published a book about the history of women cartoonists. The other was the Danish Cartoon Controversy in 2005, which I will discuss in a minute.

Why do I draw cartoons, why do others, why are there so few women cartoonists and why do cartoons cause others to kill? These questions still are forefront in my mind in part because world events have made them still very timely. Historically and presently, both women and racial minorities have had to deal with humor directed at them and it is used as a controlling mechanism.

First I would like to talk about gender and cartooning, and I would like to begin with my path, because it has informed much of my understanding.

I began cartooning when I was very little. Of course children love cartoons, and I was no exception. And I loved to draw. But what I found different about cartooning was that it made my mother smile. She had a difficult life, and it made me happy to make her happy.

This is still often my motivation—to make people happy. It also allowed me to be who I wanted to be that had nothing (or so I thought ) to do with my gender. I didn’t have to be anything but an artist.

Cartooning is also a mode of communication. I was very shy as a child, and so I found a way to talk through drawing. To communicate what I was thinking, what I was seeing; and it was almost like a journal for me, helping me comprehend the world around me.

Both of these attributes—wanting to please, and being shy–these characteristics that brought me to my profession are –I now know—gendered. As women we are taught to make others comfortable, to placate and to help. And, we are often taught—particularly in my generation—to be soft spoken and to listen, that our opinions are not necessarily needed, or of any value.

And women are taught to follow rules, whatever they are. This is changing of course, but is not completely gone.

So when we talk about creating a society that promotes equality of gender, we are talking about changing a system. Its about equal pay, equal rights, but its also about cultural expectations and behaviors. It’s a system that is perpetuated by both genders, and we need to figure out a way to change that. This is also true of other political systems.

This is where I feel humor—in particular cartoons– can help.

Let me explain

The philosopher Judith Butler writes on humor and says that the function of humor is to both solidify cultural traditions, and break down cultural traditions. Because these cultural constructs can often be very tenuous, comedy feeds off this unstable state by manipulating people’s anxiety. Humor is created out of unexpected, the abnormal, the unusual and the elicit a laugh. And so humorists rely on the traditions of a society. Humor seperates groups and individuals, but it also solidifies groups, nations, as to common practices, beliefs. But in the same way, it can enlighten as it exposes wrongful stereotypes, traditions and practices. So, on the one hand, humor brings us together as a society, but it can also show what’s wrong. Cartoons can do this, and I’d like to show you some of my cartoons about women’s rights.

As you can see: Humor can get at the daily life that women lead, a life that is always political. This is how cartoons can show and help us see how wrong some of our traditions are. Because all women have to deal with wrongful traditions and stereotypes to one degree or another, no matter where they live.

Feminist academic Uma Naryan writes on tradition and cultural construction and she talks about notion of woman as gatekeeper of tradition, mores, and cultural practices. In all countries, humor has typically been from male perspective and it has been of larger issues, such as wars, conflict, hunger, political leaders, etc.

Women cartoonists often speak from a more cultural perspective. Being closer to families, communities, children, they bring a more nuanced view of constructs that are problematic in any given society. As purveyors of the standards, women are taught from an early age (from their mothers) what the norms are, and women cartoonists are not immune from these instructions. And as women, we are taught to be hyper observant and vigilant in our behavior and dress in order to fit into our society as women. These things combined make for an artistic voice that is nuanced and close to the ground. A voice that is in tune with the peoples of a country, not necessarily simply the countries as a political institution.

All cartoonists have the ability to draw for change. Educated women cartoonists bring an understanding of world issues to their voices as women. Internationally, there are numerous feminisms. Each country/culture has it’s own, and within each country there are differing groups of feminists. Dialogue and discourse is the way to “unite” feminists, although uniting is not the desired end result. Rather understanding, acceptance and support is the end result.

Because as women, we are united while we are different. The only recourse towards equality is communication. Because of language differences, it’s often difficult. But visual communication is not as limiting (although in many cases it can be), and thus cartoons are a perfect vehicle for such discourse, or at least a starting point. This art form also provides important visual dialogue about issues of great importance to women because women are typically treated as visual “objects” in many if not all societies.

The state of women cartoonists today is still not equal. I have come to know many cartoonists who are women around the world.

I just spoke about using cartoons to communicate what needs to be changed in societies, particularly as concerns women, and how cartoons can be a way to communicate. Everyone loves cartoons and are drawn to them as children, so it is a good way to capture someone’s attention. Cartoons are powerful.

But often cartoons are hurtful. We know humor can be aggressive and make people feel either out of place, unwanted, stupid or wrong. All of us remember a joke someone told and if we did not understand it, we felt like we did not belong. Racist and sexist jokes typically are used to hurt others while bonding the joke teller to his perceived group. This is the negative side of humor: hurt and exclusion.

We have seen how this is true globally now, with two events in the last ten years. The Danish Cartoon Controversy and the Charlie Hebdo killings in France.

I remember waking up in 2005 and upon reading the front page of the New York Times, having mixed feelings about seeing the word “cartoon” on the front page, upper left corner above the fold. This is the place that top news is always situated, and I was amazed (and I hate to say it, somewhat proud) to see that word there. But horrified. This became known as the Danish Cartoon Controversy

Cartoons were commissioned by an editor at a Danish newspaper and 12 cartoons about the Prophet Mohammed were published on Sept 30, 2005, including one of the Prophet wearing a turban shaped as a burning bomb. The group of cartoons were titled, “The Face of Mohammed” and they were a variety of approaches to that topic—some benign, others strong.

In the months that followed, two of the cartoonists had to go into hiding after receiving death threats. In these first six months there were demonstrations and riots. There were some deaths but they were mostly due to violence during large unruly protests. World leaders weighed in, supporting the publication, others denouncing the cartoons, some both. It appeared to be a world trying to cope with what it meant: Do we like the cartoons, not like them, are they insulting, are they not insulting? What does the Muslim community think? What do non-Muslims think? The publication of the cartoons in late September 2005 provoked a fierce national debate over whether free speech had gone too far. Denmark, like many societies, was trying to integrate the growth of a Muslim population in their society.

Some blame the newspaper, others blame the Imams who traveled and inflamed Muslim opinion. Many see this as a clash between Islam and the West, exploited by radical forces. Others blame the largely secular Danish population for not understating the religious sensitivities of Muslims. Most agree that is was general misunderstanding and lack of information on both sides: the Danish cartoonists and editors did not realize how their cartoons would be received by some in the Muslim community, and Muslims did not understand the tradition of satire in Western cultures. And one cannot ignore the internet’s role in inflaming tensions on both sides.

But we saw how cartoons can cause immense misunderstanding.

On Oct 16, 2006 Cartooning for Peace was founded at the UN in New York. I was one of the twelve cartoonists invited to attend and give a speech at the UN about what cartooning means to me and to societies. CFP is still very active, and I am now director of the New York office and I traveling to talk about the power of cartoons and freedom of expression, and the responsibility of cartoonists. Cartoonists don’t always agree, but we all feel passionately about our work, and we comprehend it’s power. Many cartoonists believe in the absolutism of freedom of speech, and feel “political correctness” is our enemy. I am a strong believer in freedom of speech of course, but I am also a believer in respect of others.

Cartoons have to be created that walk that fine line of commentary without hate.

While the debate about the Danish cartoons died down in the public, it never really quieted among cartoonists. And last January, we saw again how cartoons can be controversial and bring others to be violent.

The satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo poked fun at everyone, every religion, culture and politician. It followed in the French tradition of irreverent satire, and the cartoonists at CH feel they are equal opportunity satirists who create humor in the name of freedom of expression. But extremists did not like what the cartoonists drew and attacked the offices and other areas of Paris and 17 people were killed.

There was incredible outpouring of support, and particularly among my colleagues. Both events made me question my profession, my place in this world and what good cartoons can be.

My belief is that making fun of extremists only fans the flames, and does no good. The cartoonists and innocent victims did not deserve to die, of course not. The extremists who shot them are responsible. The victims were exercising their right to freedom of speech, and that’s a right we need to protect.

During the outpouring of cartoons from my colleagues all over the world, many cartoonists chose to use their skills to represent the tools of our trade, a pen and a brush, as weapons. Humor can be a weapon, it can hurt others.

I try to do cartoons about world events, and I am careful. I don’t see that as negative. I do not consider myself acting under pressure to be politically correct. I see it as respectful. There are plenty of other ways to expose injustice and the wrongs of the world. Look at what happened today, 60 years ago? Rosa Parks kept her seat on a bus. That’s it! She didn’t attack anyone, threaten anyone, insult anyone. Learning to get along with our fellow humans is increasingly complicated now, and we need understanding. Cartoons can promote understanding, as they protect free speech.

Cartoons can expose the horribleness of world events, but they can also show us the politics of daily life. We can expose sexism, racism, extremism, classism. We can talk about injustice. We can take control of humor and use it not to divide, not to push people away or hurt them, but to help. Every approach is needed to make any change, because change comes from personal level, cultural level and leadership level. As we fight extremists, and as we fight sexism, we need to come at the problems at all levels. Not stoop to their level, but rise above it and use humor for good.

I like to think of my pen not as a gun, but as an olive branch.

It’s about sharing, communication, laughing together.

And, of course, fun

Recently, I was invited to travel to China to speak about editorial cartooning and women’s rights. It was an amazing experience, one that I will never forget. My host was the China Women’s Film Festival. They believe that art is a way to express important concerns and can do so in a powerful way. The people I met are brave and were very friendly, asking so many questions as we discussed how to express injustice in both our countries.

Recently, I was invited to travel to China to speak about editorial cartooning and women’s rights. It was an amazing experience, one that I will never forget. My host was the China Women’s Film Festival. They believe that art is a way to express important concerns and can do so in a powerful way. The people I met are brave and were very friendly, asking so many questions as we discussed how to express injustice in both our countries.

all the drawings I did while there in a post on my Medium page, here. And I explain the context and the people I met in a post called Under One Moon, here. I also show some of the feminist cartoons I showed in my talks in China.

all the drawings I did while there in a post on my Medium page, here. And I explain the context and the people I met in a post called Under One Moon, here. I also show some of the feminist cartoons I showed in my talks in China.