Below is the interview with Liza in Varoom Magazine this month.

“With politics firmly in the headlines both in the UK and USA, Varoom talks to four pioneering US image-makers about how the political cartoon is evolving.

For a generation of people, the caricature on the newspaper Opinion pages was a brisk corrective to what was perceived as the outrages of politicians and governments. But in an age when the printed newspaper is either closing or transitioning to digital, how is the political cartoon evolving? In a frank and provocative series of interviews published in Varoom issue 29, four exceptional US image-makers – Molly Crabapple, Jen Sorensen, Liza Donnelly and Mark Fiore – talked to us about the changing forms and contents of the political cartoon in the 21st Century.

Varoom: How has your image-making as a cartoonist changed over the last 30 years?

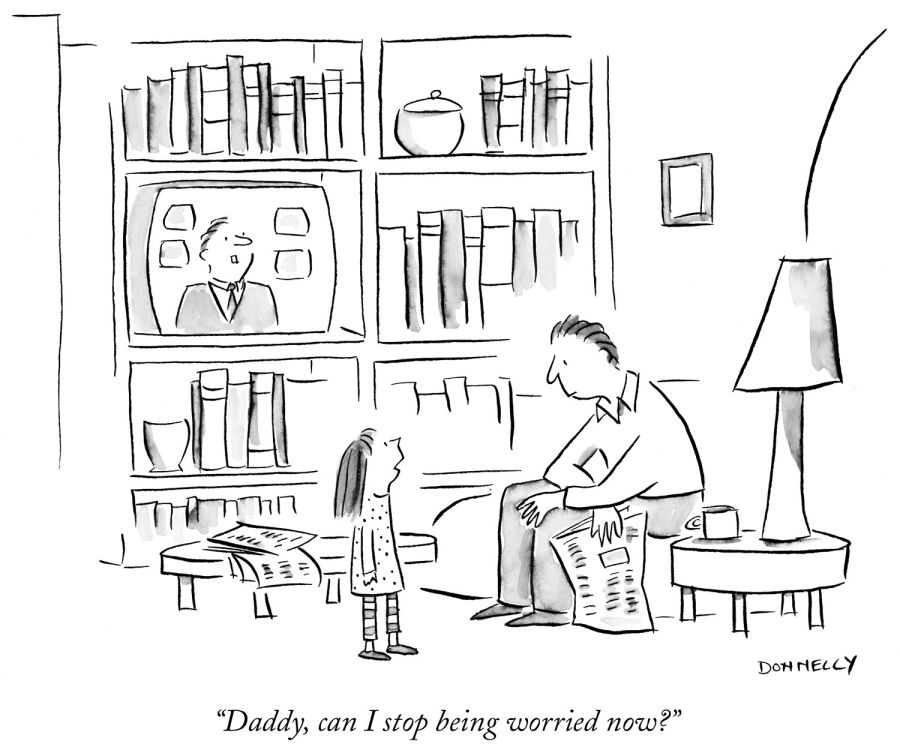

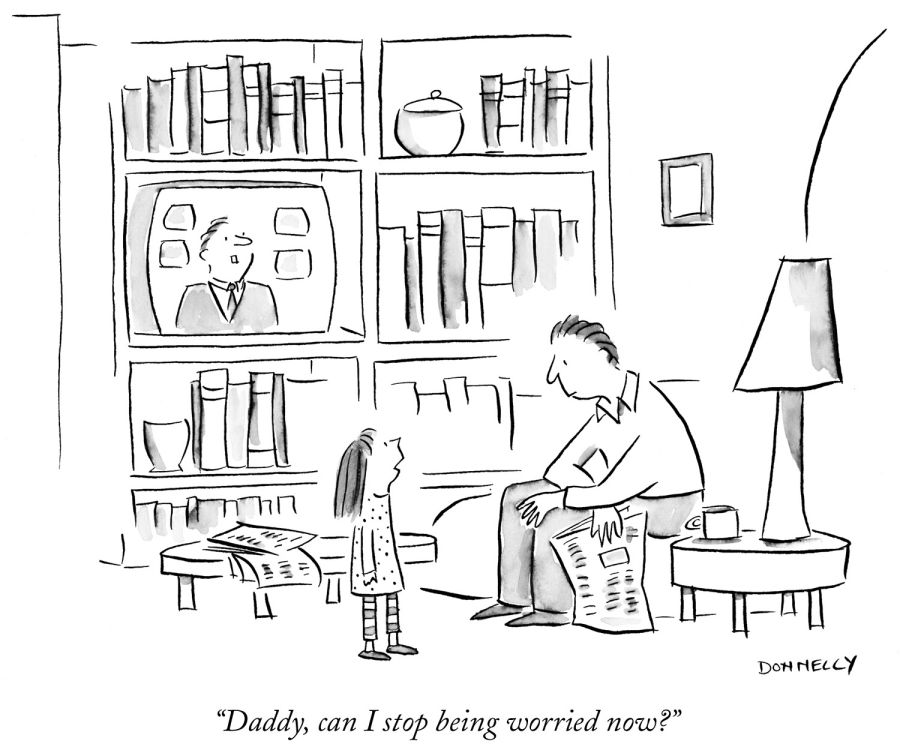

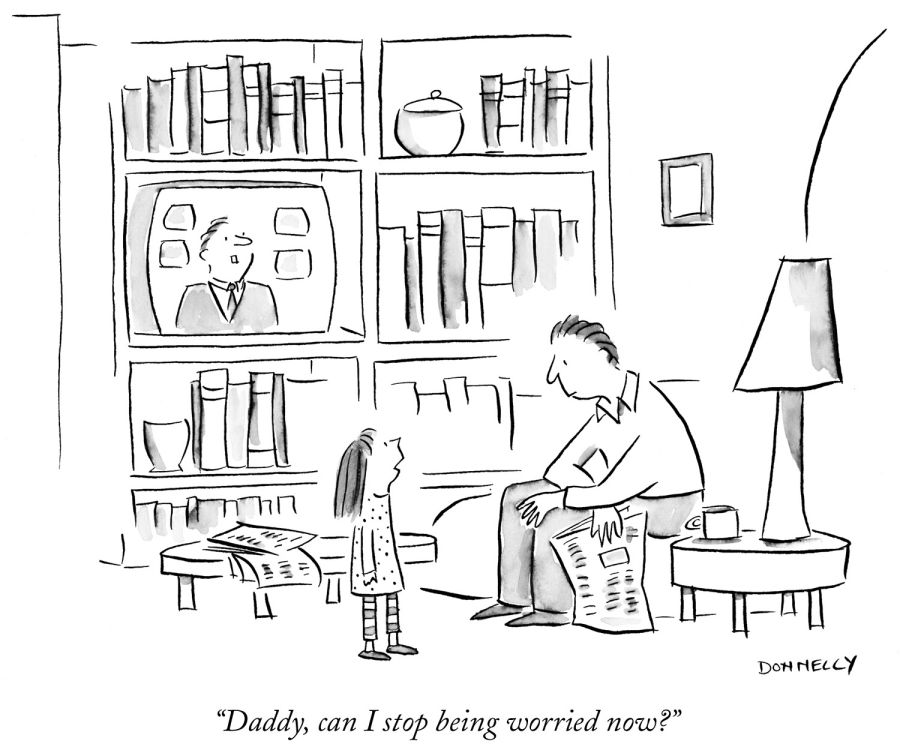

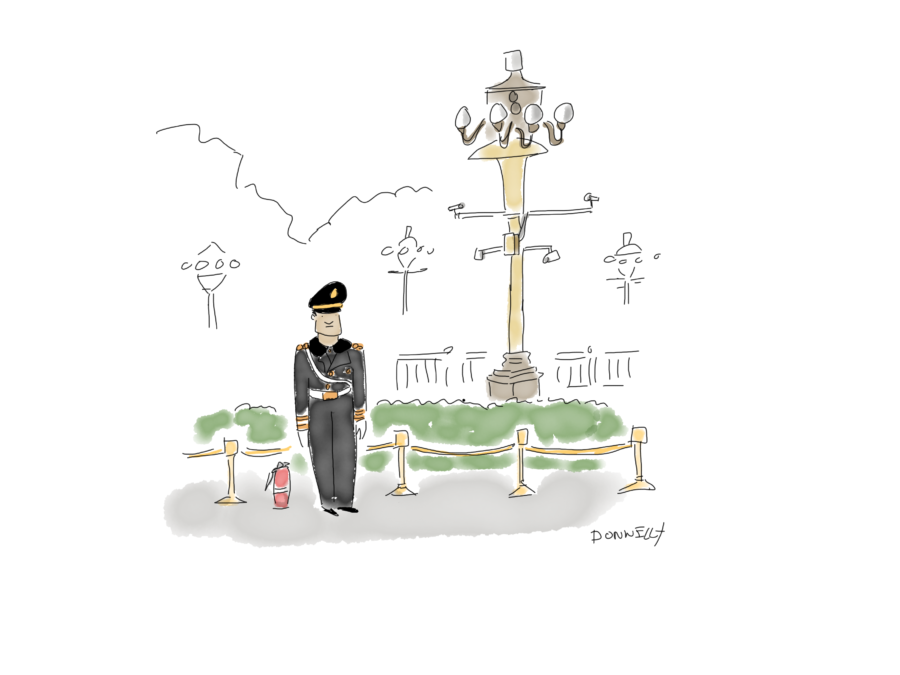

Liza Donnelly: There have been many shifts – some of them unconscious, some deliberate – over the course of my career. My early cartoons were often captionless and many of them were sequential. I got the ideas usually through drawing, and less through words. Over the years, I became more comfortable with words and used them more often, relying on captions much more, and almost exclusively. I learned to play with words and make them work with the art. My style stayed fairly consistent until the 1990s when I began drawing more women speaking in my cartoons; it wasn’t conscious, but evolved from encouragement from the editor at the time. Then after 9/11, I made a promise to myself to draw more political cartoons; I had always sold some to The New Yorker. I did more. This choice coincided with the arrival of the Internet and I soon found outlets online for my political cartoons. So now I publish weekly on the Internet, and I find Twitter is a good audience to share my cartoons with. I also use my iPad to quickly draw what I am seeing at events such as news conferences, political debates, awards shows and tweet out impressions. This has become popular and I now am getting paid to attend conferences and events to live tweet-draw things I see.

How have conceptions of ‘the political’ changed?

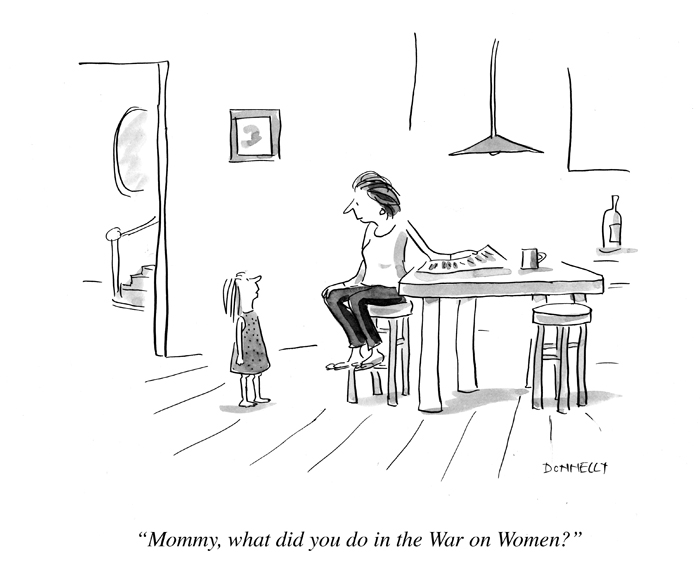

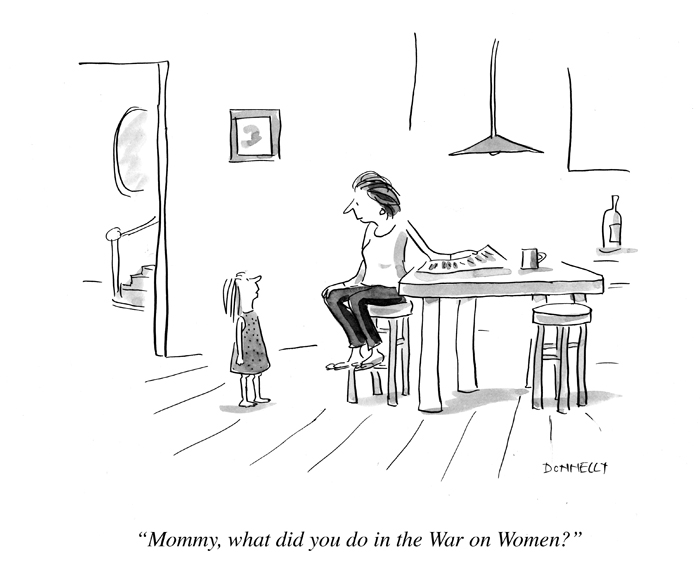

For me, political means more than just politics and politicians, but also culture. The political is how we interact with one another: racism, sexism, classism, and orientalism. Daily life can be political, particularly for women.

The New Yorker of course is the great bible of cartoons, and when you started in 1982 you were one of only three cartoonists. Were there any ‘political’ themes (in the broad sense) in your book Funny Ladies: The New Yorker’s Greatest Women Cartoonists And Their Cartoons?

Oh, yes. Most of the book consists of profiles of the women who have contributed cartoons from 1925 to the present. But a lot of the book is about their struggles doing so, sexism and other difficulties. But I also provide an overview, because when I looked at the history of the women at the magazine, I saw a trend: there were women drawing cartoons in the 1920s, but then women cartoonists disappeared in the middle of the decade, only to return to its pages in the 1970s. This follows the two waves of feminism, and is demonstrative of how freedom is conducive to creativity.

Men have traditionally dominated the world of the newspaper op-ed cartoon, the satire of a specific kind of power. Why do you think that is, and do you think women cartoonists are getting more opportunities to explore and expand the ‘cartooning of power’?

More and more women are getting into cartooning; a few are doing editorial cartooning. But it is still dominated by men. I think that the existence of the Internet is allowing more women to get their work seen, because there are fewer “gatekeepers.” But there isn’t much money in Internet publications, so it makes it harder to make a living. Historically, women have not been encouraged to share their opinions, so not unlike op-ed pieces; women have not drawn political cartoons. It’s great to see more women entering the field of cartoons, and sharing their views on global issues.

In 2012, as a cultural envoy of the US State department, you went to Israel and Palestine to discuss the political impact of cartoons in the region and international women cartoonists. What were the key insights from your talk?

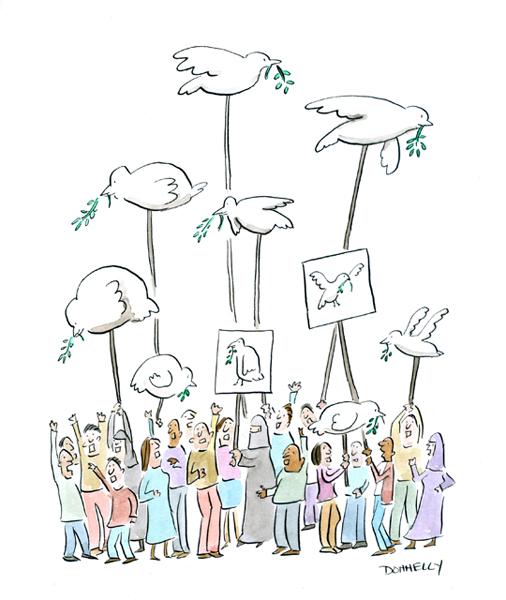

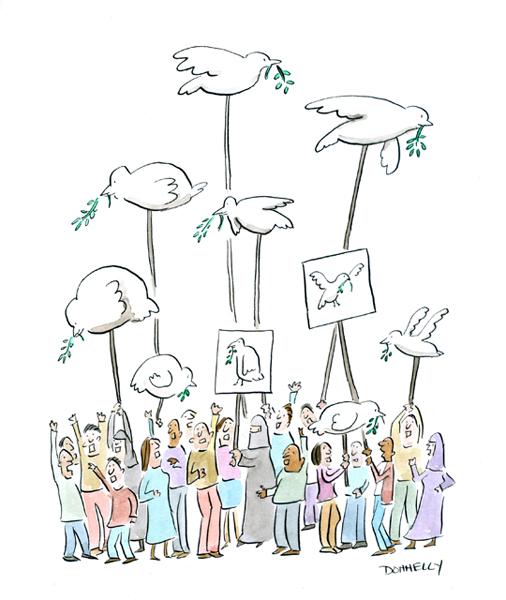

I am not an expert in any way on Israel and Palestine, so I didn’t speak about the region specifically. I don’t remember the specifics of my talks. I know, however, that I spoke about using cartoons to impact people and further dialogue. Cartoons often engage viewers in ways words cannot, as imagery can be emotional and speak to the heart and not the intellect. This is often where the power of cartoons is most apparent. I often express how cartoons can be used to bridge differences— we all laugh, so why not laugh together? Concerning women, in many cases the problems that they face are daily occurrences; cartoons can visually depict these issues and show what is at the heart of the problems through imagery. My trip to this region was quite powerful, and I enjoyed meeting with cartoonists from both Israel and Palestine, and I learned a great deal about how both sides have pressures and difficulties speaking the truth in their work. It was clear that there were pressures from the publications as well as pressures from the respective communities.

Which particular work of yours has had the most impact?

That’s hard for me to answer. I don’t really know how to measure the degree of impact my work has had. I know the talk I gave for TED in 2010 has had over a million views, and is translated into 38 languages. In that talk, I use cartoons and discuss how powerful humour is personally for me, and as a tool in the world for change. Lately, I have been doing cartoons forMedium.com that are stronger than anything I have ever done. I draw about rape and abuse in the USA and globally. I hope these cartoons are having some impact. One cartoon that had great impact on me was the cartoon I drew after 9/11. I was devastated by the attacks and wondered if I could draw cartoons again. Then I drew this one, and The New Yorker printed it. I felt very happy to be able to contribute, if even in a small way, to what had happened. That’s when I vowed to myself to do more political cartoons moving forward.

The future of ‘political’ imagery?

Respect for cartoons has never been stronger, people understand their power. We understand its limitations, and its ability to cause harm and death. Hopefully we can use the pen and ink to bring people together. I like to say that my pen is not a sword, but an olive branch.

To read Liza’s interview in Varoom, and read the other interviews, click here.

Recently, I was invited to travel to China to speak about editorial cartooning and women’s rights. It was an amazing experience, one that I will never forget. My host was the China Women’s Film Festival. They believe that art is a way to express important concerns and can do so in a powerful way. The people I met are brave and were very friendly, asking so many questions as we discussed how to express injustice in both our countries.

Recently, I was invited to travel to China to speak about editorial cartooning and women’s rights. It was an amazing experience, one that I will never forget. My host was the China Women’s Film Festival. They believe that art is a way to express important concerns and can do so in a powerful way. The people I met are brave and were very friendly, asking so many questions as we discussed how to express injustice in both our countries.

all the drawings I did while there in a post on my Medium page, here. And I explain the context and the people I met in a post called Under One Moon, here. I also show some of the feminist cartoons I showed in my talks in China.

all the drawings I did while there in a post on my Medium page, here. And I explain the context and the people I met in a post called Under One Moon, here. I also show some of the feminist cartoons I showed in my talks in China.